A drive from New Orleans along the Great River Road in Louisiana left me with three distinct images and a haunting river of thought.

Driving Louisiana’s Great River Road: The Journey Begins

When I close my eyes and think of Louisiana’s Great River Road, there are three images that really stand out.

The first, an avenue of Live Oaks, trees so stately, so green that moss and leaves tumbled down them like nymphs in the rain. Their very greenness bled into the hot southern air to define green, and only green, as the colour of the summer sky.

The second image, hours later on the flat plantation land, turned that sky into thunderous purple, with tree-branch lightning slicing through towering clouds. The rage and roar of thunder swallowed the song of the crickets, while the raindrops, fat raindrops, raised-on-buttermilk, shrimp-and-grits-raindrops, plundered down to raise the smell of life from the earth.

And the third was the silhouette of one young girl.

Haunting, hesitant, ready to tip-toe into church where bare legs would have dangled over polished wooden seats, she stands frozen beneath a white-aired watchful god. But something in her face, her slumping shoulders tells that something’s wrong.

At the age of four, or maybe five, the household inventory lists her as a slave.

And it is the only life she has – or will – ever know. And the sculpture alone is enough to break my hard-to-be-broken heart.

Driving the Great River Road

From Baton Rouge to New Orleans, the great sugar plantations border both sides of the river all the way, and stretch their league-wide levels back to the dim forest of beaded cypress in the rear. The broad river lying between the two becomes a spacious street.

Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi

Louisiana’s River Road runs from the heady mayhem of jazzy New Orleans along the Mississippi towards the state capital of Baton Rouge – and as it follows Old Man River, it sinks itself into its comfortable and uncomfortable past.

For this is where you’ll find those AnteBellum Southern mansions, all columns and land, plantations and gowns and sugary belles with blooming bustles where Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett strut, stride and simper through the undergrowth (that Gone with the Wind began in Georgia rather than Louisiana is, for artistic purposes, neither here nor there.)

Along a distance of around 70 miles, the Great River Road spans both sides of the Mississippi with mansions set back from the water, each driveway grander than the next.

One of the most well known, to undersell it just a touch, is the Oak Alley Plantation near Vacherie.

Oak Alley Plantation on the Great River Road

In all likelihood you have seen her face even if you don’t know her name. She’s graced the front cover of National Geographic, witnessed the death throes of Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt in Interview with the Vampire and even the glittery-splanged dance moves of Beyonce in her Deja Vu music video.

And when you stand on that evocative earth or throw open the doors to the verandah upstairs, it’s easy to see why.

Twenty-eight live oak trees stretch away from the 28-columned house over a quarter of a mile in a way that makes the term awe-inspiring seem worth using again.

It’s resplendent in every way, an image so inviting, combining such mastery and understanding of the land and the way geometry pleases the human eye, that the house at the end of it doesn’t register at first.

Perhaps that’s why the tour makes you start at the back, through an awkward little entrance where costumed tour guides wait with mobile phones.

Plantation Life on Louisiana’s Great River Road

Oak Alley Plantation, originally called Bon Sejour, was built in 1829 by a wealthy French Creole merchant who moved here with his French-speaking wife from New Orleans.

On the tour, a twenty-something woman in a lavender gown talks us through some of the period rooms. She points out the stylish bug-catcher kept hidden by delicate white lace and then what looks like a hanging theatre curtain that would swing back and forth to try to keep diners cool.

Outside, a horseshoe of huts illustrate other aspects of plantation life. A video details the mechanics behind sugar production, from the cutting to pressing and boiling in huge cauldrons, whose shells still pepper the house’s grounds today.

A tarpaulin stretches across a Confederate tent, with a handy interactive guide for those of us not so up to speed on the details of the American Civil War (the “South” were the Confederates or rebels, the North the Yankees or Union soldiers. They battled over state rights, including the issue of slavery, which we’ll return to again.)

But the biggest section of this part of plantation life examines the lives of the slaves themselves.

One small wooden cabin talks about laundry, another about the sick room.

America’s First Slavery Museum on the Great River Road

But as thoughtful as this section is, it is nothing, I repeat nothing to the gut punch realisation and examination of slavery that takes place at the Whitney Plantation Museum.

And it is here where I find the girl, lingering around the white-planked Antioch Baptist Church.

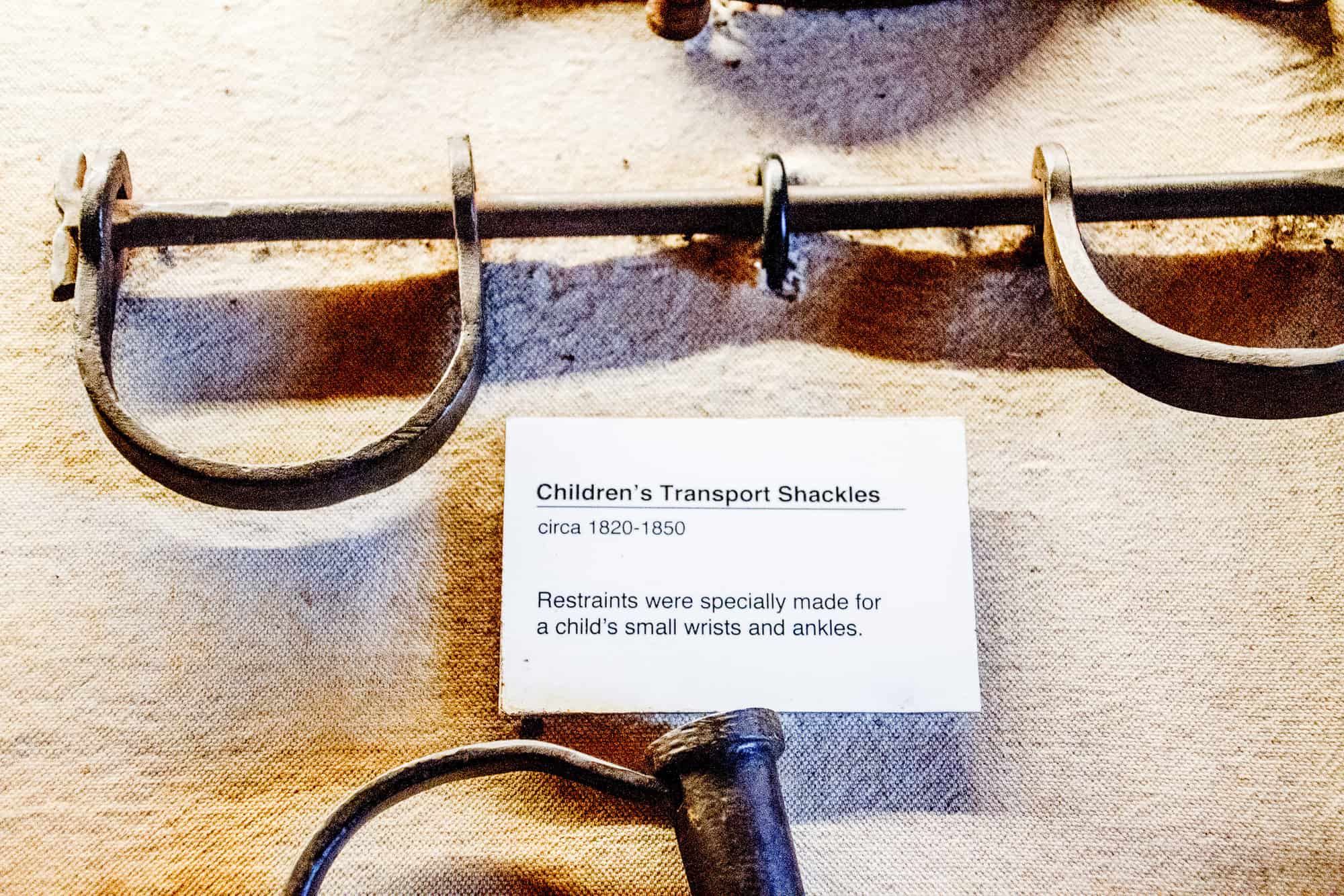

She is not alone, she is but one of a number of children, some with hats, some without, all with shoulders stooped and challenging eyes.

The Whitney Plantation in Wallace opened its doors in 2014, 262 years after its construction, to tell a different side of the story: the view of plantation life through the eyes of those who lived and worked here as slaves.

Somewhat incredibly, it’s the only museum in Louisiana of its kind. Somewhat fittingly, we arrive in the all-consuming rain.

A tall, trim woman leads a tour, a commanding spark behind her eyes.

She introduces us to the children’s graveyard, the Spanish Creole Big House, the slave cabins and the Antioch (anti-yoke) Baptist Church.

But it is the memorial wall that begins to shift my perception the most.

Or perhaps I should say memorial walls.

Reasons to Stop and Think

As the sticky rain seeps through shoes, trousers and the air we breathe itself, we hear how tours go on in all weathers because the enslaved individuals had to work in all weathers. We hear brief details about the Atlantic Slave Trade, with its triangle between Britain, West Africa and the East American Coast, and then we hear more about the trade within the States itself.

I didn’t know that plantation owners picked the strongest of their enslaved men and forced them to rape enslaved women in order to “breed good stock.” I hadn’t given enough thought to what happens when those who tried to escape were caught, how owners tagged humans in the ear and eventually sliced through hamstring flesh so that enslaved people could work but could no longer run away.

As I breastfed my baby in the shelter of a wooden slave hut, I heard how children were removed from their mothers by the age of eight and and sold off down the river.

The Great River Road and the Wall from Berlin

Those cauldron kettles I saw at Oak Alley lay discarded and pockmarked by time. A bells stood suspended on a stick. It used to signal the start and end of the working slave’s day but today it rings as a howl of remembrance for the lives that were so wretched, so wasted.

The Whitney has worked hard to dig back through the archives, to do anything and everything to give the people who lived and died here a name.

The Wall of Honor lists the origin, age and skills of those who were enslaved here on the Whitney – and it’s over 350 names deep. The Whitney then extends further, attempting to honour more than 107 000 enslaved individuals who lived and died in Louisiana prior to 1820.

We are given a period of silence, save for the slashing and crashing of the rain, to walk along these walls and pay our respects to the lives behind the names.

And perhaps it’s here, most of all, that I feel my perception seem to change.

I have, of course, always known that slavery was wrong.

I have felt it, known it, worked on it and written about it.

But here, to my great shame, I began to feel that perhaps I had never really thought enough about it.

For this wall drew natural comparisons to other walls that I had stood before.

The Berlin Wall. The 9/11 Memorial.

Questioning Slavery: A Matter of Time? Of Personal Stories? Of…?

But by the time I had reached each of those places, I’d heard story upon story, detail after detail about some of the so many individuals involved. The details of Anne Frank’s house seemed as real in my head as they were beneath my feet when I arrived in Amsterdam.

With slavery, I had nothing to hold onto, no previous life story to hold with me and guide me hand in hand.

And even here, the stories stood in fragments. Barely full names. Scarcely full places. Names that weren’t people’s own as their personal identity was too complicated, too unnecessary for commercial use.

Esther, Francoise, Zephirine.

I also began to notice, through the unrelenting rain, the different effects of language.

At Oak Alley, and perhaps in the world I’d seen before , slaves were slaves were slaves.

Slave quarters, slave labour, the slave trade.

Slaves.

At the Whitney, they were enslaved individuals, enslaved workforce, the enslaved…

Enslaved people.

People.

The invidious and insidious effects of language laid bare. Words – and names – do indeed matter.

The Power of the Great River Road

As ever, I feel in life, there isn’t the time I feel I need. And one day and one night wasn’t enough to explore the big land and the big ideas behind the Big Houses on the Great River Road.

But it was a start. An evocative, beautiful, ugly start.

Wherever we travel, we find stories of past pain. The Killing Fields from 1970s Cambodia. The enslaved people who built the white-marbled Acropolis in ancient Greece. And of course, past pain continues into the present.

Does the time that has passed change our perception of previous events? Should actions be judged in the context of their time or through the lens of indivisible human rights?

In other words, how on earth did people ever find it acceptable to treat other people in such a way?

The look from that first girl followed me past the white columns, the polished tables, the live oaks and back behind the wheel.

For those sculptures don’t depict symbolic figureheads from a dark time in history.

They represent real people.

In the 1930s, a Louisiana project sought to record the living history from everyday Americans. And that included people who born into slavery, people who had been children and young teens when the emancipation laws were finally passed.

The Whitney plays the sound of their stories, and the sculptures present their sight.

And their memories travel with me along the extraordinary 70 or so miles that run between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and back across that fateful Atlantic Ocean.

Memories from the rich, the haunting and the beautiful Louisiana Great River Road.

Where To Stay on the Great River Road

It is possible to stay on the grounds of the Oak Alley Plantation itself, in a beautiful period-decorated cottage with all the modern facilities you’d expect. I’ll tell you more about that in a later blog post, but in the meantime you can catch a glimpse of the place on the Lonely Planet broadcast over here.

Check out our nuts and bolts New Orleans Road Trip Guide – Your Ultimate Guide to Driving Louisiana here.

Also, do check out these useful tools:

Keen to travel further afield but unsure where to go? Check out our guide to choosing between Los Angeles and Miami.

More on Travel in New Orleans and Around Louisiana

To help put together your own Great River Road Trip Planner, check out our guide to driving Louisiana and our two day itinerary for New Orleans. We have practical tips, like how to understand the difference between a swamp and a bayou, to classics like the beignets of Cafe du Monde and the legacy of Louis Armstrong’s It’s A Wonderful World.

Disclosure – I travelled through Louisiana with support from a number of local CVBs and local companies, in particular Visit New Orleans, Louisiana Travel and TTM World. My trusty steed was sponsored by Hertz UK. As ever, as always, I kept the right to write what I like. Otherwise, there’s just no point.